Chimera

What makes a human distinctively so?

Even a child can sing you the answer. Diapers and crumbs, snips and snails, sugar and spice, sighs and leers. We know our fathers by their collars choke, and our mothers by their ribbons and laces.

What makes a human distinctively so?

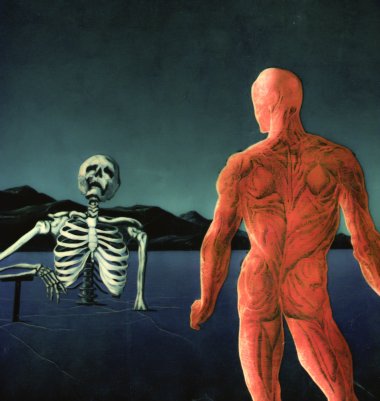

The ingredient is so protected, the trade secret so valuable, that Francis Fukuyama can only call it “Factor X.” In his 2002 book, Our Posthuman Future, Fukuyama dismembers the human on the figurative operating table, seeking our essence amidst the bones and viscera, the humors and the myths. Ultimately, he finds that no single thing—neither sentience, nor reason, nor moral choice, nor language, nor consciousness, nor emotionality—can account for humanity. But combine them just so, and we attain that ineffable factor.

What makes a human distinctively so?

If will, choice, and purpose are our distinguishing traits, as theologian Joseph Fletcher argues, then laboratory conception is as human as it gets.

Fletcher has some unlikely bedfellows. Shulamith Firestone, for one, famously wrote in The Dialectic of Sex that a woman can’t be free without freeing herself from incubation. Randy Wicker, a gay rights activist, expects cloning to make “heterosexuality’s historic monopoly on reproduction obsolete.” This is not to say that Firestone and Wicker would welcome the link; they might suspect—with good reason—that any such affiliation would turn their politics into the handmaiden of scientism…

What makes a human distinctively so?

There are more things on earth than were dreamt of in Greek mythology. The fire-breathing, interspecies chimera of lore barely compares to Lydia Fairchild: the herald of Wicker’s dream that, man or woman, gay or straight, we’ll someday gain the right to become our own twin.

Not that Fairchild had much say in the matter. A chance fusion of eggs gave her forty-six chromosomes, or two DNA signatures, effectively making her multiple people. As this condition exhibited no outward signs, Fairchild might have lived unaware that she’s what the medical community calls a chimera. But then, the law intervened.

In the early 2000s, Fairchild’s application for public assistance required her children to take DNA tests, revealing a mismatch between their genetic makeup and her own. Fairchild asserted her biological maternity, though given the results, the state suspected welfare fraud. A subsequent test, given to a baby she had just birthed, produced the same mismatch and left little room for doubt: Fairchild had multiple DNA signatures. She was, in actuality, both mother and aunt of her children.

This bizarre case illuminates a larger trend of personal testimony losing ground to genetic evidence. According to Aaron T. Norton and Ozzie Zehner, such evidence creates “technological confessions” for people like Fairchild “through a privileged objectification of their biological attributes.” Fairchild’s assertion of maternity, in other words, means little against the findings of DNA tests, however varied their results.

Yet the claim of biological objectivity gives lie to the biopolitical forces at play—to how bodies are constructed and contested by science and before the law. Transgender parents with a genetic relationship to their children, for example, occasionally find their parental rights nullified for failing to match their original sex. Genetics thus could not be called an objective force in jurisprudence. Rather, it’s deemed to be objective when aiding and abetting social norms—when affirming traditionalist thinking about identity and parenthood.

Sometimes you judge a book by its content, through usually, you just glance at the cover.

What makes a human distinctively so?

If will, choice, and purpose are our distinguishing traits, then laboratory conception is as human as it gets. But if laboratory conception increases the chances of chimerism roughly thirty-three-fold, then what we call a “human” may already be a chimera in drag. The future belongs to chimeras.

Surtsey

What had always been a likelihood became, in 1963, a reality: the state of nature leapt off the page and into the sea. More swan dive than swan song, as the cook of a nearby fishing trawler reported, the old bird proved to have some life in her yet. Centuries of philosophical bluster had kept her aloft, and her descent was just as exaggerated: the sky darkened, the sea roiled, peacetimes became wartimes, and lovers fighters…

Finally, as the waters began to settle, the diva emerged from the depths. She had fallen into a swoon on a smoking chunk of volcano.

Over the next four years, the volcano grew island-size, an upside-down comma of unspoilt perfection that nearby Iceland designated as a nature reserve. Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau must have rolled in their graves at the missed opportunity, for the Icelandic scientists did significantly less than design a social experiment. They sat on their hands and watched the wind blow, waiting for a seed, a something to happen.

The state of nature, it turns out, is a better read. Gradually, plants made their way from the mainland, but the evolutionary magic of islands—the mammoth becoming the mouse, the dwarf the giant—has not enchanted Surtsey yet. Humans are beginning to force her hand: trace tomato seeds, in a scientist’s bowel movement, later sprouted a plant; some naughty boys were caught planting potatoes. For the right price, a crooked fisherman will ferry you, under the cover of darkness, to indulge in a clandestine shit.

If this island is any indication, then the truth of the matter contradicts the philosophers’ claims: Society is not a coping mechanism for the savagery of the wild, but a novelty, a distraction from the state of total boredom.

Church

However convincingly space agencies justify the enormous budgets, there’s one gratuitous expense: training astronauts for free fall. Simply pay a visit to fraternity row, where potential spacemen routinely defy the laws of gravity.

Zero-G is the post-planetary equivalent of a keg stand. Astronauts don’t hang upside-down, but the effect is much the same: the body’s fluids congregate in the chest and head, puffing faces and pressurizing skulls. Balance soon goes out of whack; G-force makes the adrenaline flow. Continual swelling of the optic nerve causes some to become…farsighted!

For spacemen of the sixties, the poison of choice wasn’t alcohol, but drugs. In the early years of the decade, NASA commissioned two researchers to design a human best adapted to space—who lived in “space qua natura.” Their model being, astoundingly, could breath without lungs and space walk without suits.

To describe this new human, the researchers invented the term “cyborg.”

When the system didn’t function effectively, the human element was presumed to be the problem. Spacemen deprived of sensory and motor variation, for example, have been known to experience “psychotic-like states.” In such instances, the researchers advised that drug infusions be triggered remotely from earth or by a fellow crew member.

In other instances, a human could exhibit maladaptive behavior. The exogenous devices and subcutaneous tubes might be misperceived as threatening and controlling, not ingenious and benign. The pharmacological pumps, despite their avowed function, appear as “palliation” for the depressions of the cyborg complex—the anxieties of being haplessly invaded by the future.

For these (and most other) scenarios, drugs were the prescribed solution.

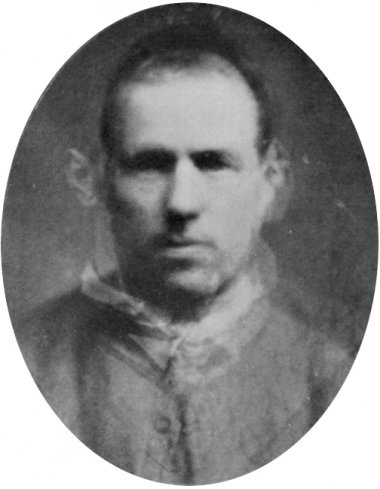

The first cyborg was thus a human freed from biological limitations, yet bound by imperfect devices and doped to ease the pain of those imperfections. In the decades since, genetic engineering has been learning to fix such problems on the assembly line. Speaking at a 2014 symposium, George Church—the man who gives the field an avuncular face—identified gene variants pertinent to survival in extra-terrestrial environments: LPR5 G171V for extra-strong bones, MSTN for lean muscles, GHR for lowered cancer risk, and so on. Future generations won’t suffer come-downs or crushing hangovers; they’ll be built to party from our solar system to wherever.

Shara

A few years ago, a group of UFO believers approached Shara Bailey, an anthropologist working on dental morphology in hominins and early humans. They claimed to have found an ancient jaw of tantalizingly unknown provenance…

Shara agreed to talk with the television reporter covering the story, stating something to the effect of: “In my professional opinion, this jaw is a fake. There’s nothing on earth that looks like this.”

Her first sentence was cut from the broadcast segment. Shara has been a darling of the believer community ever since.

Telepath

Nothing under the sun, no matter how unbelievable or fantastic, is immune to the pressures of evolution. Take science-fiction. The Force, the mind meld—the entire field of psionics, for that matter—have the look of yellowing comic books, the taste of stale popcorn. They would have gone the way of the dodo, if not for the magic of capital. Hollywood has proved to be more powerful than natural selection, building menageries in the form of franchises, gilding cages for endangered ideas. The future has never been better preserved; the future has never looked older.

It wasn’t always this way. What had historically loitered around myth and spiritualism, as second sight and sixth sense, only approached the field of science in the 1930s. Laboratories began to run experiments in “extra-sensory perception,” tasking subjects of exceptional ability to guess cards from a custom-made deck, or “receive” drawings at a distance, then recreate them by hand.

ESP drew still more interest from science-fiction writers, whose protagonists could deploy their psionic powers far beyond the lab. Still, these abilities came at a cost; the crippled, the deaf-blind, and the mutant were frequent recipients. Our brains already monopolize the body’s energy reserves, and additional fuel must come from somewhere…

Psionics plays several roles in the sci-fi imaginary—most politically, as the binding force of a group mind. One community in Robert A. Heinlein’s Methuselah’s Children, for example, makes no distinction between its members, who collectively manipulate the genetics and ecology of their world. The group mind, in this scenario, bypasses the strictures of possessive individualism and breaks with social norms. Brains may be bigger or smaller—may belong to different genders, races, and creeds—but they all have a place in the noosphere.

Alas, such ideals are rarely forthcoming, and like many technologies of the twentieth century, psionics found immediate application in warcraft. Spurred by reports of psychic training on the far side of the Iron Curtain, the CIA funded two initiatives, beginning in the 1970s, to practice “remote viewing.” Early prototypes of drones, these psychic spies flew the extra-sensory airstreams, scanning for enemy bases, terrorists, and missing fighter-bombers. Their success rate was better than what a pigeon photographer would have achieved, but not sufficient to keep the program intact. It ended in 1995, conceding defeat to the ascendant machine eye.

The Cold War was a renaissance of psionic sci-fi, before “espionage” became “counter-terrorism,” when secrets lent themselves less to torture than to telepathic extraction. But the genre changed with the times. We no longer need to imagine a group mind, because we’ve found one in cyberspace, nor wait for telepathy, as telepathy-like machines will do. We might find irony in the fact that disability—once a seeming prerequisite for ESP—now gets support from these machines, wherein a thought can move an avatar arm, or reach brains in other countries as quick flashes of lights, to be decoded as digits, then letters. Perhaps it’s time to revise that famous phrase: She thinks, therefore I am.

A moving arm, a flashing light may be as far as we get. Miguel Nicolelis, who predicted the coming of “neurosocial networking,” doubts that emotions, memories, and higher cognitive states will ever be capable of transmission. Could it be that these qualities, so integral to our notion of self, are resilient to telepathic capture? Is the soul digging trenches and fortifying ranks?

Or is this a matter less of the soul than of the science of individuation, which holds that no two brains are exactly alike, and thus no thought can share the same neuronal position? If so, then achieving a group mind would require a feat of Borgesian proportions: seven billion, four hundred million dictionaries to be written with the means of translating between them. Before the printing press, we enslaved ourselves to transcription; soon, transcription may enslave the machines.

Dreyfuss

What is the shape, the size of democracy? It’s bigger than a breadbox and smaller than a planet, too much for the individual and rarely enough to fit a nation, like a mismatched lid on a boiling pot that lets the steam escape.

For the 1939 World’s Fair, Henry Dreyfuss scaled democracy as a city, purpose-built with good intentions. Each and every resident could enjoy a garden apartment, a bucolic view, the landscaped highway to his job downtown, the landscaped highway for a swift retreat. “Democracity” claimed to depict the world in a hundred year’s time, though suburbia was just around the corner.

What is the face, the figure of democracy—life lived on the 50th percentile? Over the following decades, Dreyfuss zoomed in from his greenfield city to the intimate lives of its users: from utopian theater to the science of ergonomics.

His 1955 book, Designing for People, all but confirmed this shift, casting “Joe and Josephine” as paragons of mid-century gender. Their machines, like their mores, dictated how they should fit (no matter the aches and injuries). Dreyfuss earned his reputation by improving the machines.

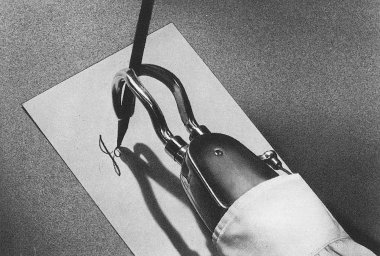

Joe and Josephine pass their days, respectively, on a linotype and over the ironing table, then in a tank and at the switchboard. He loses a limb. She routes a call. When Joe returns from the war, he finds his blue collars bleached. Starched and pressed Oxfords hang in the closet, ready for office work. And his stump, to his surprise, is a distinguishing mark—a plaque in need of a medal. In the 1940s, Dreyfuss was contracted by the Veterans Administration to design just the thing.

Joe wears his medal to work each day, the stainless steel hooks peeking out from his cuff. On occasion, he’ll roll up his shirtsleeve to his coworkers’ delight, revealing the single housing, the hidden joints, the subtleties of the prosthetic’s engineering. If only they had a war hero’s life; what an honorable disability!

Smurf

There was a time when you couldn’t find the Smurf village without being led by a Smurf, and even then, the journey was considerable. Mountains, deserts, marshes, and forests encircle “The Cursed Land” they call home.

Isolation, it seems, yields utopian results. Absent are the instruments of economy, the myths of individuality forever keeping us at arm’s length. Everyone has a strength performed to communal effect; none lacks a bed in a mushroom.

The Smurfs should be happy, and yet they’re blue. A smile tells one story, and the skin another. Does the seclusion, the inbreeding make them so? The strain of maintaining a utopian life? Or the recognition that, socialists or not, they’re the essential ingredient for turning matter into gold?

Nowadays, you can visit without needing a guide. Somewhere in Kentucky, near the towns of Hazard and Troublesome Creek Times, is the human equivalent of “The Cursed Land.” Its Smurfs—or “Blue Fugates”—pale in comparison to their cartoon peers. They’ve been blue since 1820, but are fading every day: whenever a newcomer dilutes the dye, whenever an exit is paved.

The Fugates are a textbook case of the “founder effect,” or the impact on a small, isolated community of its founders’ genetic stock. As genetic variation decreases over the course of generations, recessive traits come to the fore, like the syndrome that gives some Amish extra fingers and toes, or the one that causes many girls from a village in the Dominican Republic to sprout penises around puberty. Ernst Mayr, an evolutionary biologist, has boldly claimed that changes brought on by the founder effect can lead to speciation!

The founders of the Fugates, Martin and Elizabeth, shared a genetic condition called methemoglobinemia, which makes the blood produce a surplus of hemoglobin that is unable to release oxygen into the body. Living in geographical and genetic seclusion (albeit with more than one Smurfette), their progeny had no choice but to be blue.

This tree grows sideways and byways, not onwards and upwards. “You’ll notice,” said one descendent, that “I’m kin to myself.”

Guppy

We are getting stupider.

Over the past 20,000 years, our brain has shrunk by roughly the size of a tennis ball, diminishing the most valuable resource on the planet. Though the organ is left with some gray matter to mine, gone are countless cognitive potentials for the making of a better human.

The problem is domestication. As primatologist Richard Wrangham has shown, the brains of domesticated animals are ten to fifteen percent smaller than those of their peers in the wild. Wrangham suspects that in selecting against aggression, we’ve inadvertently favored creatures with juvenile brains.

Beyond the world of pets, domestication goes by another name: “the social contract” that constricts our freedom, keeping our savagery at bay. Those few who protest the captive life—Nietzsche’s “more complete people” (read: “more complete beasts”)—are made the exceptions that prove the rule. A breeder decides which dog will live on through its litter, and capital punishment, which human will die.

We are getting smarter.

A big brain was the Mark 1 of cognitive processors, housed in a Cro-Magnon case. For all the energy guzzling, it had little to show. The massive muscles of its hominid, more by habit than smarts, moved backwards from predators and forwards to prey.

The real measure of the brain isn’t size, but cellular and molecular complexity. Neural density correlates to computational capacity. True, our organ is growing larger again with the benefit of good nutrition, but if it demands too much energy, the rest of the body will suffer, blackouts rolling across the biological grid.

Consider the guppy. In 2015, researchers ran an experiment selecting for female guppies with larger brains, finding that their gains in mental ability correlated with with dwindling gut sizes and reproduction rates. No wonder the top-heavy humans of fictional futures are often infirm from neck to toe.

Sometime in the next two thousand million years, our brain will be mapped and painstakingly known. Human enterprise has been working towards this moment, when at last, we can see all the quirks and crannies, the limitations, the cartoon brick walls. We expected to find such imperfections; unfortunately, we had never imagined the scope—never conceived that our minds, shown with perfect clarity, would fall so piteously short of the heavens.

In time, we concede the point: If there’s no improving the human brain, we’ll build a better human to build a better brain.

Our prototype is an exaggeration, even by homuncular standards. Embryonic manipulation yields a brain twelve feet in diameter, vaguely attached to a diminutive body. Whatever the intellectual gains of growing so large an organ, there are equal losses in autonomy. This “better human” will live an unhappy few years, at the mercy of bioregulation machines, until obesity does it in.

Eventually, we perfect our design, the organ spreading through a forty-foot diameter turret, its gyri collecting in various pockets. Lord of the concrete tower, Übermensch manifest, this “Great Brain” is even more demanding than its prototype, requiring so many resources that we turn into voluntary slaves, toiling away for our idol.

The “Great Brain” can venture far into the wilds of the mind, where savageries of thought live unbeknown to the greater world. Yet all the while, its body is static: the turret a jail, the pockets like cells. How little there is to life when you’re a prisoner to intelligence…

In time, the brain designs a prototype, setting mind and body in better proportion. If there’s no improving the “Great Brain,” build a better human to build a better brain.

Great Chain

The Great Chain of Being, that marvelous convenience linking lowest to highest, the dialogues of Plato to the satires of Pope, began as a divine provocation.

Some way into The Iliad, as Greeks and Trojans stood on opposing margins of a blank page, Zeus decided to issue a warning. Any gods who lent their penmanship to the war would suffer no less a fate than exile. And any attempt to overthrow his authority—to latch a chain to the heavens and drag him down—would be tantamount to folly. He was too powerful to budge.

Moreover, Zeus threatened that with a mere tug of the chain, he could send the rebel gods flying, the carnal world pulled in their wake. Their instrument could easily become his plaything—a necklace to hang around the peak of Olympus.

Zeus never acted on these words and grew forgetful of his gauntlet, ever less a challenge and ever more a chain. Nature, too, had forgotten: gradually, its denizens found shelter in the links, growing accustomed to the altitude and the elliptical life. As moss grows on a rock, so the natural world took to its host, until the two were impossible to distinguish.

Gods came and went, and still the chain kept hanging—no longer the bauble of a boastful god, but the instrument of a wise one. Elizabethans seeking evidence of the Almighty’s plan needed look no further than this object, in which everything had a place. The ugliest stone, the poisonous animal, the treacherous snake, and the louse could not be errors of creation, because each got its designated link. So, too, did the beggar and deaf mute have their place in society, provided they stuck to it.

Everything—even angels—filled the chain, though complex hierarchies abounded. Wild beasts were superior to domesticated ones for their resistance to human training. Avian creatures bested the aquatic, as surely as air’s domain sits above water’s. In the insect realm, the beautiful ladybug ranked nearly as high as the bee, whose kingdom provided a social allegory. The chain’s links usually ended well before Hell, lest the sinners attempt to climb.

Man held a special position in this chain. On account of his wit and will, he stood one link above the beasts and yet, owing to his carnal form, one shy of the angels. By the eighteenth century, his position had become ever more suspect, for undoubtedly the lowliest angel was far superior to man! The scholars found themselves in a quandary: conceding the point would break the chain, while ignoring it bordered on hubris. And so, in a prescient act, links were added and planets imagined, home to beings that could bridge the gap. Unlike the extraterrestrials of our age, those of the Enlightenment weren’t foreign to humankind; they fit hand in glove with its logics.

Baby

What is the face, the figure of humanity—life lived on the 50th percentile? We can’t define the deviant without first inventing the “norm.”

This concept joined the social sciences, in the mid-nineteenth century, through the work of Adolphe Quetelet. Drawing on biological and criminological data, the statistician sought to determine the physical and moral qualities of “the average man.” A harbinger of the eugenics movement, this “man” was an empirical fiction who grew less lifelike and less precise despite the addition of quantitative information.

Quetelet’s model made skeptics of people like Francis Galton, because it implied that taller, smarter, and morally superior individuals also deviated from the norm. Galton responded by devising his own model, one that emphasized the median over the mean, or in other words, where one stood in the rank, not who comprised the average. The norm here became less observed than ideal: an aspiration for social betterment that gave cause for selective breeding.

“The average man” was the first of the century’s many hallucinations, culminating with Galton’s attempt to visualize the biological aspects of the “criminal type.” The resulting images, composited from multiple photographs of unique individuals, were received at the time as optical equivalents of large statistical tables. They showed the faces of true evil to be data manifest.

Composite photography went the way of many nineteenth-century pseudosciences, growing as obscure as the hair and ears of its subjects. Nowadays, though digital technology can intensify this technique—pixel by pixel, layer upon infinite layer—the norm no longer lives on the surface of images, but deep in the grain of the self.

Thanks to The Human Genome Project, we’ve at last revised the “rough draft” of humanity, producing a “‘consensus’” DNA sequence that, David Serlin qualifies, is, “like all composites, a fiction.” What, after all, defines the normality of a genome in constant change?

By sequencing and patenting our genes, we follow in the footsteps of Quetelet: adding data to “the average man,” observing the scope of deviation. Engineering the perfect human, however, requires a leap in Galton’s direction. Just as Galton had to rework Quetelet’s model, in justifying eugenic practices, so too must genetics do more than plot and “explain” our genome, by claiming the authority to improve its every last fault.

What is the figure, the future of humanity—life engineered for the 50th percentile? In assimilating to the genomic norm, we’ll forgo much more than deviance. Genetic diversity will lessen, and vulnerabilities increase: minor viruses that grow to epidemic proportions, endgames that prey on our lack of divergence. The tree, stripped of its branches and leaves, will memorialize something we’ve forgotten to remember.

Quaddie

“Quaddie” is a term awaiting political correction, but how else should we describe the four-armed workers genetically engineered for free fall environments?

The Quaddies are the legal property of a mining company. As “post-fetal experimental tissue cultures,” they’re too many links down the Great Chain to share human rights and protections.

A Quaddie body is bottom-heavy: thin hips atop massive glutes. The lower arms are bowed and muscled, the wrists thick, the digits squat. It’s what you get when you put a chimpanzee on a horse, then remove the horse.

Seat

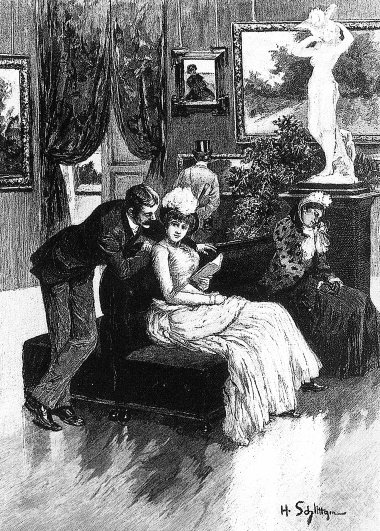

At one time, for practical reasons, the heating systems of museums found lodging in their sofas. The ottoman of the Louvre’s Salon Carré—that infamous object from Henry James’s The American, where the art of seduction was ever on display—contained a coal grate to keep bodies and passions inflamed. In warmer seasons, when the libido can more or less heat itself, such seats became park benches: resting stops for “aesthetic headaches” as much as for wearied amblers and would-be picnickers.

Contemporary museums, in contrast, are decidedly less commodious. We still chance upon a sublime artwork from time to time, then stumble back in disbelief, yet rarely are our Stendhal swoons caught by plush upholstery. A wooden bench might break our fall, or a daybed on holiday from its analyst. More often than not, we hit the floor.

The museum seat is one in a constellation of display structures that increasingly cater to the “disembodied” spectator. This peculiar human, comprising merely two eyeballs and a brain, began haunting museums as early as the mid-nineteenth century—and prompting shifts in institutional design. Joel Sanders and Diana Fuss have traced the seating of London’s National Gallery, for example, which began in a private residence in the early century, where furniture could be moved at the viewer’s discretion. However, once the Gallery relocated to the heart of the city, only a few chairs remained, implicitly fixed in their positions. An engraving of the era depicts viewers familiarizing themselves with the new norm; they stand, they look, and they contemplate.

By the time MoMA opened its doors in 1939, the disembodied spectator had assumed modern airs, no longer soft-shoeing in search of moral education, but flowing through the galleries like a shopper through a department store. Amidst this marvelous circulation, the museum seat appeared increasingly lost: a relic of the time when a body could suffer the exhaustion, an eye the strain, that it uniquely relieved. The first MoMA benches came with backs, but those would disappear soon after, reducing the museum seat to a signpost for significant artwork—an entreaty to give a little more from our shrinking attentional wallets.

Nowadays, a few museums in the world carry new types of seats, as uncomfortable as MoMA’s ascetic units, albeit for a very different reason. Ergonomically designed for future bodies, they prescribe corporeal norms that no living human can fit. And so they’ll wait, like the museums themselves, until these bodies come along to fill them…